Mr. Misang is a Seoul-based illustrator and animator whose work explores the individual's position within the anonymous structures of contemporary life. His densely composed scenes depict crowds, cities, and bureaucratic systems not as backgrounds but as active forces—environments shaped by desire, routine, and infrastructural logic.

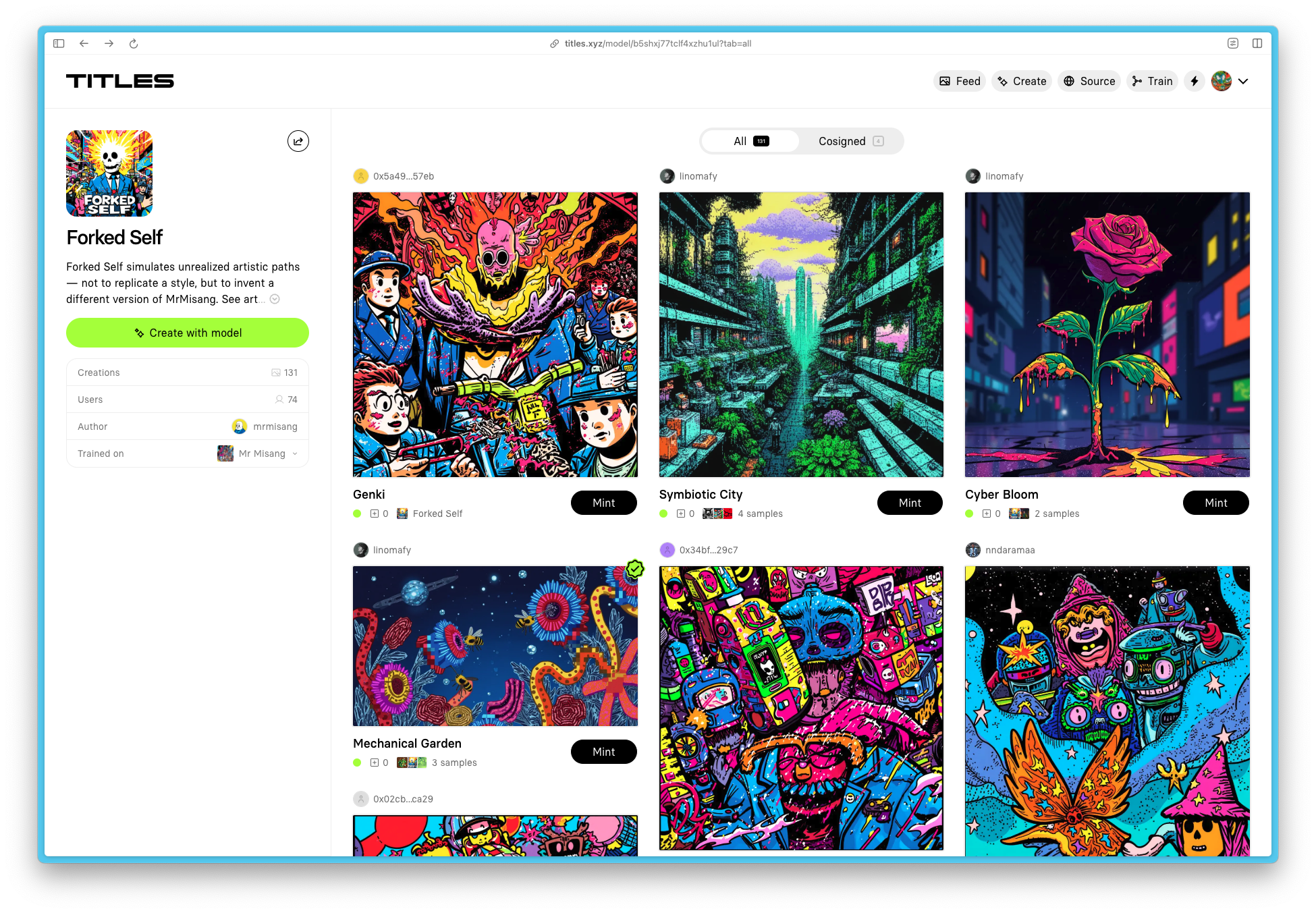

Forked Self, Mr. Misang’s model with TITLES, is trained on two separate bodies of work—one more recent and one comprising pieces created between 2010 and 2021. The result is not a replica of his current style, but a speculative exploration of how his visual language might have evolved along a different path.

Your name Mr. Misang references anonymity, misang meaning "unknown" in Korean. Why is anonymity such a central theme for you?

In my illustrations, the characters almost always appear as part of a crowd. But when you fix the camera on a single figure, that person suddenly becomes the center of the world. Move the camera just a little, and they disappear back into the masses. The crowd is a constellation of vast, unseen universes. And each of those universes doesn’t need to have a name. For me, anonymity is a way of exploring the position of the individual within that structure. The name ‘Mr. Misang’ embodies both anonymity and collectivity.

Your illustrations often treat the environment—the city, the crowd, the architecture—as the main character. What draws you to this broader, systemic view of modern life?

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera writes that beneath the surface of city life, a sewer system sprawls out like tentacles. Ever since I encountered that line, I became more conscious of the complex systems that support the world. These could be urban infrastructures or the physical laws that govern the universe. Similarly, within the system of society, people often function as parts of a structure, and at times, they are consumed by it. Still, I’m not trying to evoke a tired narrative of “individuals sacrificed for the whole.” I simply mean that, when you zoom out far enough, the world is actually structured in that way. Buildings are massive totems constructed from desire. And desire has a face. If something has a face, the camera will eventually make it a protagonist. So when you zoom out over a city, it’s only natural that these totems of desire become the central subject of the frame. Zoom in again, and it’s the crowd. Closer still, and you’re looking at an individual within that crowd. In the end, everything begins with a single question: Where do you place the camera?

How do you think about the emotional tone you establish in your work?

When I plan a piece, emotional tone isn’t my top priority. There are other things to solve—layout, color, subject. Emotion emerges naturally from my current state, and lightly seeps into the entire surface. I don’t feel the need to control the shape of that spread.

But this question made me pause and think about myself—as someone who works. I’m always tired, but I keep walking. And strangely, this has little to do with whether the work succeeds. I experienced something like burnout ten years ago, in a major way. I don’t think I’ve ever fully recovered from it. But still—I keep doing the work, and I will keep doing it.

Looking back, most of the characters in my work are thrown into the world. They don’t know exactly where they’re headed, but they move forward anyway. Sometimes they get swept up by the wave of the crowd; sometimes they try to resist it. But the important thing is—they are always walking toward somewhere. Maybe that’s how I live too.

Your illustrations are incredibly intricate and surreal. What does your process look like when you are constructing these worlds and what do you draw inspiration from?

I grew up surrounded by countless images. I admire too many artists to list here. Those images exist in fragments—blurred, shuffled—somewhere in my mind. When I begin a piece, trying to express a certain theme, those fragments surface and recombine. It’s not like I get a perfect mental snapshot all at once. (I’ve heard some artists do. That’s a superpower I envy.)

What I see is something hazy—an accumulation of impressions. Those impressions, shaped by moment-to-moment decisions, gradually become a composition. There are infinite paths to placing an object or a color, and I use my full intuition to keep choosing the most promising ones. Whether I always choose the “best” possibility—I don’t know. But this process is what happens every time I make a piece. Each work reaches completion through intuition, selection, and compromise.

I find this process strikingly similar to how AI generates images. Both human intuition and machine decisions have gaps that can’t be fully explained. But my conclusion is simple: If the result works—if it’s beautiful—then that’s enough.

How do you see technology impacting the behaviors and environments you depict? How do you see virtual space interacting with physical space?

Technology doesn’t appear directly in my images, but it surrounds them. Blockchain and NFTs have long wrapped around my digital work. Because technology always becomes normalized over time, I don’t think it should be the core of the work. What matters is always the content and expression.

I’m deeply influenced by technology in ways that exist outside the image itself. For example, I’ve had countless conversations with ChatGPT. Thoughts that would’ve evaporated unstructured are shaped and refined through this back-and-forth. Not all of those conversations are about my work. But when I structure a messy trail of thought into something coherent, it often circles back and influences me again—just as the images I’ve seen, music I’ve heard, or books I’ve read continue to affect my work. I find this constantly expanding self-reference incredibly enjoyable.

My AI model, Forked Self, was shaped by these dialogues. It isn’t designed to replicate my current style. It explores alternate pasts—possibilities I never pursued. I think that kind of conceptual approach offers a different kind of pleasure from pure technical fidelity. And TITLES’ approach—linking the original training works to on-chain NFTs—felt like a meaningful way for artists to retain authorship in the age of AI.

I do have a past work that touches on the interaction between virtual and physical space—MrMisang & Crypto World, a 2D animation. In that piece, I explored the relationship between three distinct layers: virtual images (digital artworks), virtual space (a crypto gallery), and physical space (the viewers outside the screen).

The main character moves freely between these realms. He leaps out of a digital image on display, roams around the virtual space, and interacts with it dynamically. At the end of the piece, he breaks through the boundary of the virtual world and emerges into physical space.

If this work serves as my response to this question, then I’d put it into words like this: “The distinction between virtual and physical space is meaningless.” Though honestly, I’m not entirely sure I believe that myself. You can watch the full piece on my website.

What draws you to digital technology in the way you produce and distribute your own work?

I probably first encountered web-based drawing tools and Photoshop when I was in elementary school. From that point on, digital became my primary tool quite naturally. The only times I worked analog were when I didn’t have access to digital—like during military service—or when digital tools weren’t yet as convenient as they are now, like before drawing tablets and iPads were widely available.

A Ctrl+Z environment became a constant in my creative process. The colors on the screen felt more beautiful precisely because they could be undone. Of course, there were times when I didn’t have that luxury. During those periods, I created highly detailed pen drawings on paper without the option to revise. Some of those pen works—like the line art for Space Hardrock Machine, which I drew during my military service—were even used to train this Forked Self model. Once I committed to pursuing a “perfect screen,” the ability to reverse became essential.

I’m an artist who constantly reflects on the past while moving toward the future. The only medium that allows me to divide versions and rewind time is digital. In that sense, my immersion in digital work feels like a natural outcome.

What does it mean for you to have your own model on TITLES?

Possibility. This model is an experiment in following the paths I never walked. It’s also a framework that allows the artist to decide which works are used for AI training. For the audience, it could become another entry point—one that expands my work in ways I wouldn’t have predicted. Try Mr. Misang’s model on TITLES, here.

Closing

We’re so excited to see what each of you dream up with Mr. Misang’s Forked Self model. If you enjoyed learning about the story behind his practice and model. Please take a moment to follow him on Twitter, Instagram, and TITLES.

Much love,

- TITLES